Water, one of the most fundamental human resources, is facing a depleted supply worldwide amid the rapidly intensifying climate crisis. A newly published report found that the world is experiencing an “unprecedented water crisis” due to the growing population and global warming events, with one-quarter of the world facing extreme water stress every year.

—

An Unprecedented Water Crisis

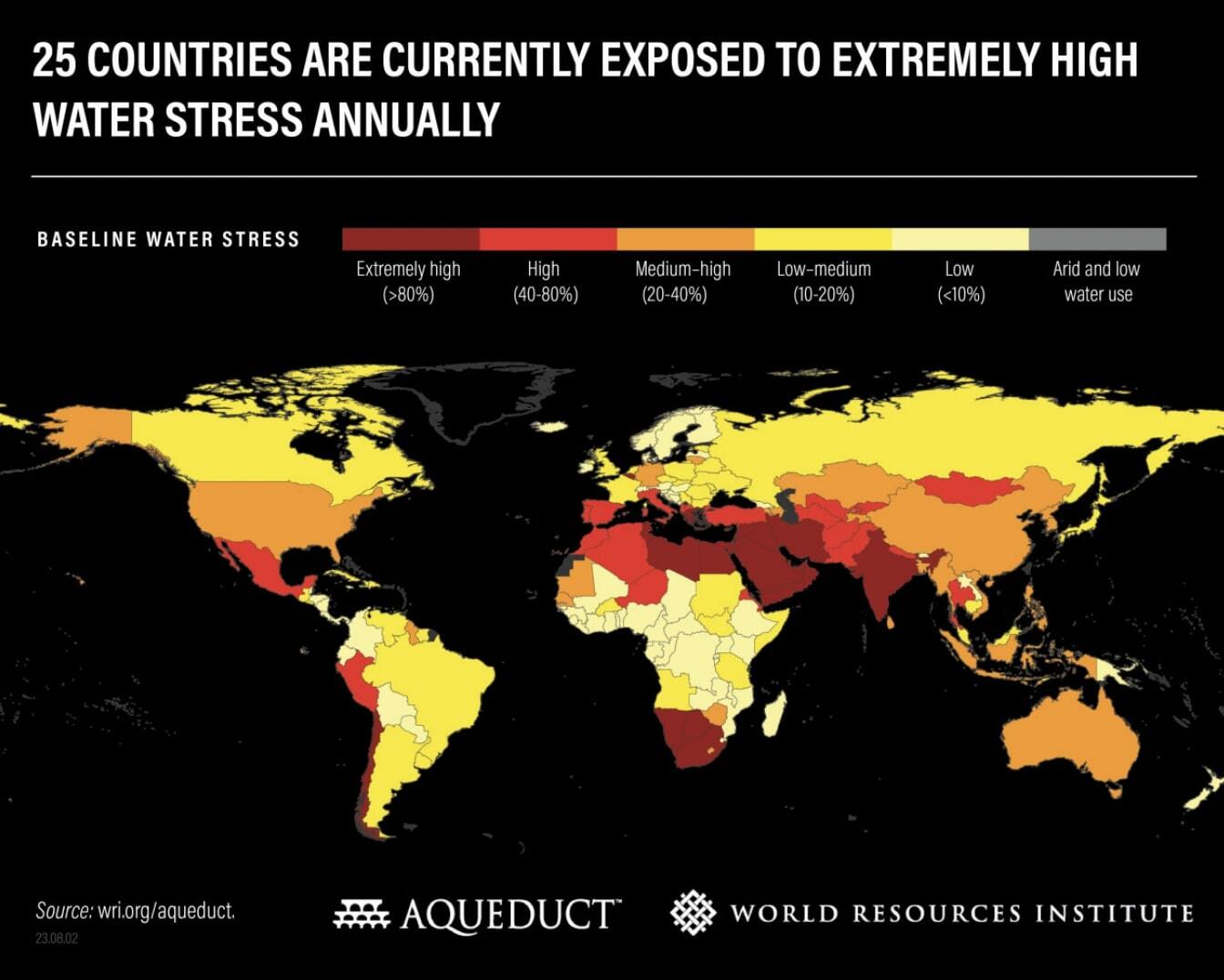

A recent study conducted by World Resources Institute’s (WRI) Aqueduct Water Risk Atlas found that 25 countries, equivalent to approximately one-quarter of the world’s population, are going through “extremely high water stress” every year. The top five countries with the highest water stress levels are Bahrain, Cyprus, Kuwait, Lebanon, Oman, and Qatar.

As explained in the report, “extreme water stress” means the country is using at least 80% of its available water supply, while “high water stress” indicates that it is withdrawing 40% of its supply.

Researchers behind the study, which was published in August 2023, also predicted that about 60% of the population will be affected by water stress for at least one month per year by 2050.

A world map showing countries with varying levels of annual water stress. Image: World Resources Institute.

The water crisis does not simply involve water. The report found that 31% of the global GDP will be negatively affected by extreme water stress by 2050, and industrial interruptions will occur more frequently due to limited water coolant. Moreover, the water crisis is already putting food security in serious jeopardy, as 60% of the world’s agriculture faces high water stress. This water stress phenomenon is perpetuated by the growing demand for water due to the rapidly growing global population. Indeed, experts suggest that the agricultural output needs to expand by another 70% by 2050 to meet the growing demand for food.

The misuse of water resources also plays a significant role in the decreasing drinking water supply. Prompted by the fast-paced corporate and business agendas, sewage and waste from industrial sites and agricultural practices have been mishandled and directly ejected to fresh streams, contaminating drinking water and making it unfit for human consumption.

While the contamination from the agricultural and industrial sectors is indeed extensive in straining our water supply, the current water shortage is most exacerbated by the increasingly severe climate change-related extreme weather events unfolding across the world in recent years.

Our Planet Is Getting Hotter and Drier

Global warming has taken a toll on our planet this summer, with this year’s June being the hottest June ever recorded. Meanwhile, this year’s July was the world’s hottest month since records began 174 years ago, accumulating four record-breaking temperatures of the world’s hottest day. Though July 4 was ultimately deemed the hottest day on record with a global average temperature of 17.18C (62.92F), experts agree that the record might be broken again very soon as global warming intensifies.

The heat has been undeniably growing more intense in recent years. Last month, UN Secretary-General António Guterres declared that we have gone beyond the stage of global warming and have entered the era of “global boiling.”

Unprecedented heatwaves and devastating wildfires have made headlines nearly every single day over the course of this summer. The Maui wildfires claimed nearly 100 lives on August 8 and completely destroyed the historic town of Lahaina. A few weeks before that, wildfires tormented regions in the Mediterranean, engulfing entire cities in Greece, Algeria, and Italy’s South. The death toll across the three countries exceeded 40, while tens of thousands were displaced.

On August 17, 2023, local French authorities reported that a heat dome in France could result in the nation’s “most intense heatwave ever.” The high temperature and minimal precipitation in the country have contributed to a sharp decline in water supply, leaving over 30,000 residents in Southern France with no “reliable water sources” due to the severe drought.

Intense heatwaves also occurred in China, as the nation logged a temperature of 52C (126F) in its northwest region on July 17, breaking its previous record of 50.3C (122.54F). Its capital city Beijing recorded its hottest June day in 60 years, with temperatures soaring to 41.1C (105.9F). Additionally, local media reported that accumulated precipitation in northern China from June 2023 to August 2023 was 30% to 70% less than normal, implying that droughts in those areas will persist until the end of August, putting a strain on local cultivation of livestock, maintenance of hydropower supplies, and crop irrigation.

The dwindling water supply has evidently grown to be a global problem. As the World Bank puts it: “Climate change expresses itself through water.”

How Do We Stop This?

Climate change has forced us into a vicious cycle of heatwaves that have been drying up our water sources. Despite it all, we still have a chance to turn things around.

To improve the situation, the WRI report suggests preserving wetlands and forestry to improve water quality, subsequently reducing expenses on water treatment. This could also help “build resilience” against droughts and floods. Prioritising “water-prudent energy sources” like solar and wind power, instead of wave, tide, and hydroelectric energy sources, would also go a long way in preserving the water supply.

Another noteworthy point is the fact that agricultural practices can be altered for water conservation. For a reliable, short-term solution, more drought-tolerant crops, such as figs, okra, and grapes, can be harvested to consolidate food security. But for more long-lasting effects, techniques like drip-irrigation could be widely adopted. Drip-irrigation uses pipes to slowly drip water onto the roots of crops, conserving 20% to 50% of the water typically used for irrigation.

There are even more specific steps that can alleviate water scarcity and extreme water stress. Most notably, a proper and well-managed green infrastructure can be sustained. The report suggests that for water governance to be improved, policymakers must adopt an integrated water resource management.

Bahrain, crowned as the most water-stressed country in the world, has several flaws in its water management system. For example, Water Action Hub found that the entire nation has no rivers, lakes, or dams, a factor that significantly limits access to water. Therefore, the country sought water from the ground, which prompted a “sharp decrease in groundwater storage” that resulted in the degradation of more than half of its reservoir.

In contrast, some other countries are leading the way, such as South Korea, which adopted a smart-water management system, a network comprised of reusing, properly treating, and delivering water to end users. Recently, the US also announced plans to invest in water infrastructure in the Upper Colorado River Basin in hopes to enhance Western communities’ resilience to drought and climate change.

With continuous and proper management, we can adequately maintain our water supply. We must remember that having enough water does not simply equate to quenching our thirst, but also ensuring food security, fighting urgent disasters like wildfires and heat-related illnesses, and maintain adequate levels of sanitisation.

You might also like: The Future of Farming: Can We Feed the World Without Destroying It?