The Wildlife Trusts has recently reported that prescribing time in nature for those with mental health issues can make significant improvements to their wellbeing. With an ever-growing population and an increasing disconnection with nature, can immersing ourselves in nature improve not only our mental and social wellbeing, but our inclination towards environmental conservation as well?

—

The world is rapidly urbanising- already 55% of the global population lives in urban areas, a number projected to rise to nearly 70% by 2050 according to the UN. With that, time spent in nature is often reduced. Research has found that less time spent in nature threatens future conservation efforts – termed the ‘pigeon paradox’. Under the current urbanisation status quo, this means that interactions with urban natures, organisms and ecosystems – pigeons, mice or squirrels, for example- characterise many people’s perception of nature. At the same time, those who are active in conserving the environment most often cite childhood experiences with nature as critical prerequisites for subsequent environmental actions.

The paper bases its ‘paradox’ on the assertion that the future of conservation efforts depends on our current interactions with urban green space, as spending time within nature grows an intrinsic care for it and therefore provides an impetus for its protection. As such, the paper argues for the critical importance of restoring urban ecosystems and promoting urban green spaces for everyone to access: the future of conservation requires it. Bringing the natural world to more of the population in the urban sphere thus has critical importance, both for conservation but also health benefits – particularly as most of us spend 90% of our time indoors.

How does nature affect mental health?

In 2017, The Wildlife Trusts’ report entitled, “The Health and Wellbeing Impacts of Volunteering with The Wildlife Trusts” found that amongst those with reported mental health issues, 69% of those who spent time involved in environmental conservation projects felt an improvement during a six week period. Built on by research with Leeds Beckett University and The Wildlife Trusts, social return on investment (SROI) from promoting Wildlife Trusts’ conservation programmes for health benefits was found to generate a return of £6.88 for every £1 invested. Such a result illustrates the imperative need for investments in green spaces in cities as well as in conservation volunteering schemes. Specifically to the UK, this will reduce the burden on the National Health Service and improve daily wellbeing amongst the population. According to Anne-Marie Bagnall, Professor of Health and Wellbeing Evidence at Leeds Beckett University, “The significant return on investment of conservation activities in nature means that they should be encouraged as part of psychological wellbeing interventions.”

Why Nature is Good for Your Mental Health

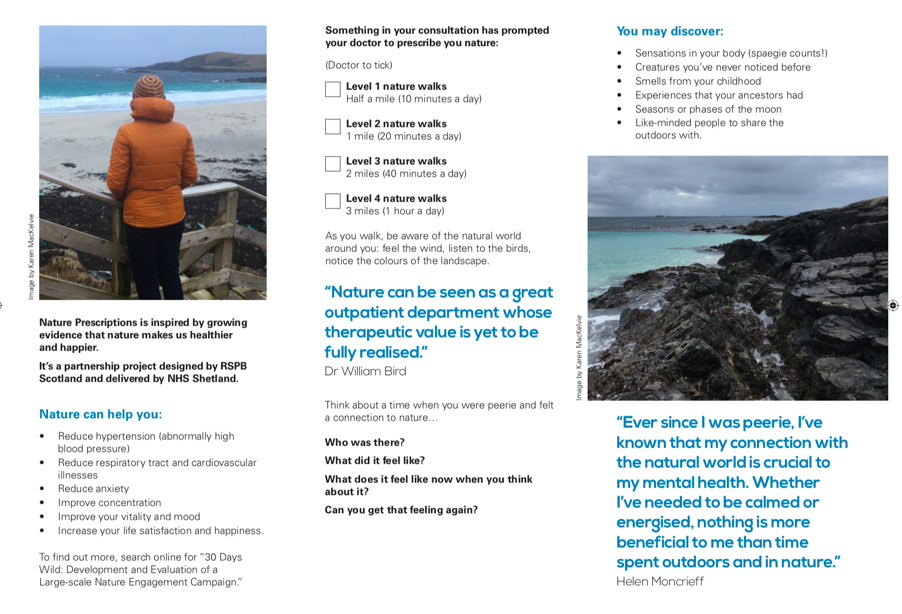

So, are such ‘nature prescriptions’ set to take off? Academic literature supporting the link between better health outcomes– lower stress, anxiety levels or heart rate– and more time in nature is growing. Nature prescriptions are being slowly introduced in the US and UK. As one of over 150 programmes in the USA, California’s Stay Healthy in Nature Everyday (SHINE) group, takes groups of patients, doctors, and naturalists to local parks each month for a dose of nature. The Royal Society for the Protection of Birds (RSPB) Scotland has recently launched its partnership with NHS Shetland for ‘Nature Prescriptions’, while ‘Myplace’ in Lancashire, a specialist in ‘ecotherapy’, has found a 100% increase in wellbeing from its attendees.

The trend seems to be catching on: doctors elsewhere in the UK have been encouraged to suggest that their patients get outside, supported by the Centre for Sustainable Healthcare in Oxford. The centre’s NHS Forest project aims to increase patients’ use of local parks and woodlands near hospitals and health centres. A study from Scientific Reports finds that only two hours per week is needed to reap nature’s calming benefits. One health trend that is popular mainly in Japan and South Korea is Shinrin-yoku, or ‘forest bathing’. Dr Qing Li, a Japanese expert in forest bathing, argues that the traditional Japanese practice- spending intentional time within trees- can promote health, happiness and wellbeing through reducing blood pressure, strengthening cardiovascular systems and boosting creativity.

Nature’s benefits are endless: As artist Andy Goldsworthy says, “We ARE nature. Nature is not something separate from us. So when we say we have lost our connection to nature, we’ve lost our connection to ourselves.”

More time in nature can improve not only our intrinsic care for it, but also our own health and wellbeing. At the same time, promoting the benefits of nature, particularly in the urban realm, provides a larger incentive for tree-planting and urban garden initiatives– ultimately mitigating climate-related issues. This is one way that cities can work towards achieving Goal 11 of the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals for 2030 that focuses on ‘Urban Sustainability’.