News media and advertising have historically been inseparable. Together, they have shaped how the public absorbs content. News outlets rely on advertising revenue, and ads placed on the pages of widely read newspapers present significant market advantages for companies. Modern integrated advertising techniques have adapted to the digital era, and present a more unobtrusive experience for readers. Major fossil fuel corporations have benefited from the subtle nature of integrated advertising in modern news media by blurring the traditional boundaries between advertisements and legitimate journalism. These companies hinder the efforts of independent environmental journalism by producing intentionally misleading information that greenwashes their practices. By allowing fossil fuel corporations to run integrated advertisements on their pages, news publishers are allowing these companies to spread their own narrative on climate change.

—

The practice of native advertising has a long history in print news media. The advertising technique is a form of paid media, financed by an external company but produced by the news outlet’s branding unit. These units produce ads that fit within the format and design parameters of the publisher’s regular editorial content. The result is a branded form of content, and a more subtle advertising experience for readers.

While native advertisements vary depending on the publisher and the content being advertised, they generally take the shape of an article, infographic, video or an interactive post. The advertisement will normally be accompanied by a note indicating that it contains sponsored content, although to a casual reader, it is otherwise virtually indistinguishable from an editorial piece.

The benefits of native advertising as opposed to more traditional banner ads are that they offer a more discreet advertising experience for readers and a greater audience and market reach for companies. Studies have shown that consumers are 25% more likely to engage with native advertisements than with banner ads, and 32% more likely to share a native ad with others.

The ubiquitous nature of advertising in print journalism means that even historic and well-recognised publishers rely on advertising revenue. Publications such as The New York Times and The Washington Post (NYT and WP, respectively) welcome both banner ads and native advertisements, the latter of which are produced by the publications’ branding studios, which are entirely separate from the newsroom and editorial content creators.

Criticisms of native advertising surround the blurred lines that can exist between a publisher’s independently produced content and its paid advertising, as far as the reader is concerned. Native advertisements are often expensive and compelling productions, and their wide audience reach attracts the advertising teams of deep-pocketed corporations. In this regard, fossil fuel corporations are no exception.

Fossil fuel companies such as ExxonMobil and Chevron began employing native advertising tactics long before print media began transitioning to digital formats. Ads financed by these corporations enjoy the massive audience of a newspaper’s readership and can be difficult for consumers to distinguish from editorial content, however they undermine publishers’ credibility and science-based environmental journalism. These advertisements appear in a variety of forms and mediums, and primarily attempt to greenwash fossil fuel corporations by disinforming audiences and falsely claiming that their products, practices or policies are environmentally friendly.

Some major news publishers have acknowledged the dangers of promoting pro-fossil fuel content on their platforms and have taken the necessary steps to distance themselves from these companies. In January 2020, the Guardian became the first major global news outlet to officially ban fossil fuel advertising. Smaller news outlets, such as Sweden’s Dagens ETC, have made similar decisions. By publicly recognising the risks of allowing fossil fuel corporations to spread their own narrative, news outlets can validate concerns about the overbearing reach of fossil fuel corporations in the media. Further action from major publishers can legitimise their environmental journalism and establish an uncompromising stance on climate change.

Historical Influence of Fossil Fuel Corporations on Environmental Journalism

In 2014, the Guardian, the NYT, the Wall Street Journal, and USA Today all began running native advertisements. The WP ran its first native ad in 2013.

Despite the relatively recent foray of major publications with diverse political orientations and target audiences into native advertising, these news outlets have produced content for fossil fuel corporations for decades. Native advertising can be considered the internet-age equivalent of a bygone advertising technique known as the advertorial.

Advertorials, also known as op-ads, are paid ads that mimic the design of legitimate articles in print newspapers and magazines. These ads are designed to emulate the visual elements of the publisher’s formatting, such as the font, headline style and column layout. Crucially, these ads are often placed adjacent to the newspaper’s opinion section, further blurring the distinction between legitimate content and advertisements. These advertisements often read similar to editorial pieces as they promote a specific position or opinion while reporting on a study or a product. Most advertorials feature a note indicating that the content is sponsored and by whom.

Fossil fuel corporations such as Exxon and Mobil (known collectively as ExxonMobil after their 1999 merger) have sponsored advertorials in the NYT since at least 1972, running until 2004. NYT advertorials have touted fossil fuels as the only practical fuel source for the foreseeable future, cited fringe scientific studies dismissing climate science as inaccurate and unreliable, demonised international efforts to coordinate reducing emissions and outright lobbied for pro-fossil fuel policy measures from incoming presidential administrations.

You might also like: UK Pledges an End to Financing for Overseas Fossil Fuel Projects

Image 1: On the right, an example of an advertorial sponsored by Mobil in an August 1997 issue of the NYT. The advertorial is strategically placed next to an op-ed that criticises then-President Bill Clinton’s use of a line action veto as an overreach of executive power. The advertorial admonishes the President’s administration for a lack of transparency and economic foresight in the buildup to the Kyoto Protocol signing; New York Times Editorial Pages; August 14th 1997. For the complete image, click here.

[A Greenpeace project collected 99 advertorials run in the NYT by Exxon, Mobil and ExxonMobil between 1972 and 2004. For the full list, click here.]

Fossil fuel corporations have framed advertorials as opinion-based articles, placing them alongside thematically similar op-eds and designing them as visually indistinguishable from regular editorials. Through these methods, companies have been able to greenwash their own image for decades.

Fossil fuel companies made a strategic decision in selecting the NYT to run its advertorials. In 1978, Herb Schmertz, PR executive for Mobil, discussed his tactics with the American Management Association, stating that: “The [New York] Times was chosen because it is published in the nation’s leading population, communications and business center; because it has a highly intelligent, vocal, sophisticated readership; and because it reaches legislators and other government officials,” adding that the advertorials “stimulated discussion among influentials on both sides of the issue—exactly what the company had set out to do.”

Advertorials proved highly successful in fossil fuel corporations’ lobbying efforts for three decades. However, with the advent of the internet, advertorials faded into irrelevance. Digital news models were widespread by the late 2000s, and the traditional column format that served advertorials well became obsolete. Additionally, the number of people who primarily received their news from social media began to eclipse those who continued to rely on print news publishers.

Despite the technological transitions, fossil fuel corporations proved resilient. The symbiotic relationship between news and advertising was durable, and as traditional advertisements and banner ads proved unsuitable or unprofitable for digital news outlets, publishers inevitably turned to branded content and integrated advertising alternatives, including native advertising.

Branded Content in Digital-Age Journalism

In the internet age, many high calibre news outlets have taken deliberate action to maximise the revenue opportunities afforded by advertising on a digital platform. In 2014, the NYT established its T Brand Studio, a unit that creates custom content and produces native advertisements. The WP has a similar unit known as the WP Brand Studio, also founded in 2014. As with advertorials, branded content through native ads aligns with the house style and format, although tend to take some artistic license with illustrations and graphics.

Content produced by branding studios is often innocuous and focused on general culture. A 2018 WP native ad sponsored by the Embassy of Italy highlights top Italian travel destinations and directs readers to the embassy’s website and visa services. Branded content can also incorporate socially impactful stories, such as a 2016 NYT native ad sponsored by the Netflix show ‘Orange is the New Black’, which demonstrates how the incarceration system in the US was never designed to account for the different needs of female inmates.

Crucially, these studios are unaffiliated with their publisher’s newsroom or editorial office. The “separation of church and state” in journalism refers to the boundaries that traditionally exist between the editorial and business sides of the news, specifically that business interests and economic incentives will not disrupt a news outlet’s independent journalism. In 2014, NYT T Brand Studio representative Felix Krueger stated that “There is zero editorial/advertising crossover. This is something which is strictly maintained.”

While there may be no crossover between editorial and advertising teams from the publisher’s perspective, there is often no real distinction between the two for the reader. A 2018 study on the effectiveness of native advertising found that fewer than one in 10 digital news readers were able to accurately identify content from news outlets as advertising. The study also concluded that readers who were unable to recognise native ads often did so because publishers had not clarified that the content was of a commercial nature.

The appealing and discrete nature of native advertisements, regardless of who or what is being advertised, is apparent when viewing native ads sponsored by fossil fuel corporations.

In 2018, the NYT T Brand Studio released a native ad sponsored by Chevron titled “How abundant energy is fueling U.S. growth.” The advertisement describes the economic and environmental strengths of the natural gas industry, depicting it as the only fuel source that could reconcile global energy demand with concerns over rising emissions. The ad features a slick side-scrolling design, complete with colourful illustrations and dynamic infographics, ending with a link to a page on Chevron’s website detailing the company’s commitment to natural gas.

A 2019 WP Brand Studio native ad, titled “Why natural gas will thrive in the age of renewables,” was sponsored by the American Petroleum Institute. The advertisement declares plans of transition towards 100% renewable energy use as overambitious and logistically impractical. The advertisement cites statements from fossil fuel representatives and lobbyists, criticising renewable energy as financially and technologically infeasible. The advertisement concludes by touting natural gas as a permanent solution, featuring a quote from Don Santa, CEO of the Interstate Natural Gas Association of America: “We’ll see a continuing role for natural gas—even if it shifts over time—not just as a bridge fuel but as a foundation for the future.”

Both of these advertisements recognise that a shift to sustainable energy sources is necessary, although they greenwash their own practices by depicting natural gas as a sustainable and even permanent solution. A 2019 study by Oil Change International renounces the classification of natural gas as a ‘bridge fuel.’ Increasing the capacity for natural gas will make the goal of achieving energy sector decarbonisation by mid-century unachievable. The ads fail to account for the falling costs of wind and solar energy production which will disrupt the business model for gas in the energy sector. Additionally, should renewables require another energy source to balance out energy demand and grid reliability, there is no reason for natural gas to act as the balancing fuel. Battery storage is already competitive with gas infrastructure built for this purpose, and the technology is advancing at an exponential rate.

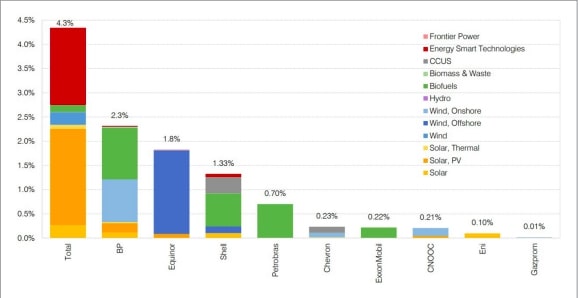

A 2018 NYT T Brand Studio ad, sponsored by ExxonMobil and titled “The future of energy? It may come from where you least expect,” features a brightly illustrated “article” accompanied by two short-form videos. The ad discusses ExxonMobil’s research and development efforts concerning algae and plant waste biofuels. The videos are compelling, featuring stop-motion animation and a youthful-sounding narrator. The advertisement paints ExxonMobil as a progressive and forward-thinking innovator of sustainable energy and low-carbon fuel alternatives. As shown in the graph below, between 2010 and 2018 ExxonMobil invested only 0.22% of their capital expenditures on low-carbon fuel solutions.

While these ads are designed to be appealing and easily digestible for readers, they mislead their audience by greenwashing corporate practices and minimising the importance of eliminating fossil fuel use. Fossil fuel corporations may well be pursuing sustainable solutions, although in reality these activities make up a miniscule fraction of their operations. The graph below shows how major fossil fuel companies have, on average, invested around 1% of their capital expenditures on low-carbon technology between 2010 and 2018.

Figure 1: Shojaeddini et al.; Disclosed low-carbon investment as a proportion of total CAPEX (2010–Q3 2018). Includes asset finance, M&A and venture capital spend. Progress in Energy; 2019.

The goal of native advertising campaigns for fossil fuel corporations is to mislead and confuse audiences on the best path forward for energy consumption. While advertorials focused on delegitimising climate research when the science was still in its nascent stage, modern native advertisements tend to acknowledge the risks of fossil fuel use and its contribution to climate change. However, fossil fuel corporations aim to mislead consumers on the effectiveness of renewable energy and distract the public from the real damage being perpetrated, allowing them to continue their harmful practices with minimal backlash.

Contradictions in Environmental Journalism and the Role of News Media

The content produced by news companies’ branding studios and financed by fossil fuel corporations is intentionally misleading, and has been since the age of the advertorial. Exxon researchers internally acknowledged the dangers of continued use of fossil fuels as early as 1977, well before the general public had even considered the possibility of anthropogenic climate change, but did nothing.

A 2017 analysis of ExxonMobil’s advertising in the NYT from 1977 to 2014 found that the spread of disinformation and doubt grew as the scientific and public consensus on climate change became entrenched. The study shows that, during this period, 83% of peer-reviewed papers and 80% of ExxonMobil’s internal documents recognised the reality of anthropogenic climate change. However, only 12% of the concurrent ExxonMobil advertorials run in the NYT did the same, with 81% actively expressing doubt or invoking fringe theories on the validity of climate science.

Despite climate change disinformation being passively perpetuated by advertisements and branding units of high calibre publishers, the newsrooms of these outlets have delivered groundbreaking environmental journalism.

NYT reporters Lisa Friedman and Hiroko Tabuchi were the 2019 recipients of SEAL Environmental Journalism Awards, celebrating their work reporting on climate change impacts and solutions. The NYT was also the recipient of the 2018 John B. Oakes Award for Distinguished Environmental Journalism, celebrating the publisher’s “Trump Rules” series for holding federal agencies accountable for environmental rollbacks under the Trump administration. This past May, the WP was awarded a 2020 Pulitzer Prize for Explanatory Reporting for its “2°C: Beyond the Limit” series, a groundbreaking and science-based series that pioneered the use of temperature data over almost 170 years to demonstrate the global reality of extreme climate change.

This contradiction is one that is difficult to reconcile. It clearly speaks to the print news media’s need for revenue, and to the excess of capital in the hands of fossil fuel corporations. In 2018, the total revenue of the US oil and gas industry was $181 billion. Meanwhile, global circulation and subscriber revenue for print and digital news outlets is expected to fall from $58.7 billion in 2019 to $50.4 billion in 2024.

Neither does this contradiction arise from a vacuum. News outlets are increasingly starved for revenue, and the profits from integrated advertising models have proven irresistible. In 2017, 27% of news media companies had a dedicated native advertising team, up from 20% in 2016, and native advertising’s share of total ad revenue is expected to rise to 22% by 2020. From 2007 to 2018, the fossil fuel industry spent $1.4 billion on advertising.

Figure 2: Brulle et al.; Annual promotional spending of major fossil fuel companies between 1986 and 2015; The Guardian; 2020.

To an extent, these figures are a sobering indication of where the market’s prime concerns lie, and where governments choose to place their concessions. These figures suggest an economy that prioritises supporting the interests of the single largest contributing industry to climate change over the needs of investigative and independent environmental journalism.

The Guardian’s move to ban fossil fuel advertising is a critical step. It proves that truth-seeking and autonomous environmental journalism can survive without the fossil fuel industry’s financial support, and should be a catalyst for other major publications to follow suit. Anna Bateson, the Guardian’s acting chief executive, and Hamish Nicklin, its chief revenue officer, addressed concerns over finances and outlined the company’s priorities in a joint statement:

“The funding model for the Guardian – like most high-quality media companies – is going to remain precarious over the next few years. It’s true that rejecting some adverts might make our lives a tiny bit tougher in the very short term. Nonetheless, we believe building a more purposeful organisation and remaining financially sustainable have to go hand in hand.”

By publicly denouncing the support of fossil fuel corporations, news outlets can muzzle misleading narratives, improve their own credibility and disrupt the ideological battle being waged by the fossil fuel lobby. Global media outlets such as the NYT, the WP, and the Guardian are important and influential actors in the fight against climate change. Policymakers and the public alike both rely on free and independent environmental journalism to investigate and reveal the true impacts of climate change, ideally without accommodating oil and gas ads posing as legitimate stories. The stories these outlets relay matter, and the onus of discerning between reliable journalism and sponsored advertisements is not one that should fall on readers’ shoulders.