Why do unsustainable industries continue to have so much influence and traction in modern markets? Fossil fuels continue to dominate energy mixes in many countries, and the majority of the world’s population continues to be affected by increasingly severe pollution rates. Market forces are not necessarily to blame, as seen by the exponential decline in costs of using renewable energy. A litany of outside forces and machinations hide the true costs incurred by unsustainable industries, supporting their bottom line and obscuring their transgressions. Certain government subsidies, championed by advocates as a policy instrument to make goods and services more affordable for consumers, finance the interests of unsustainable economic sectors, like fossil fuels, and contribute to concealing the real costs paid by consumers.

—

Government subsidies, a form of financial aid or incentive governments extend to a specific industry or business, can be considered a type of externality, wherein some of the costs of production, consumption and investment remain unaccounted for and are not reflected in the final price paid by the consumer.

Subsidies can often be a positive externality, when the financial incentive provides benefits to a third party. This is often the case when governments support businesses or industries that are not particularly profitable but provide a high social benefit, such as public housing, healthcare and education.

Other subsidies, however, finance activities that incur adverse and unintended consequences for consumers and society at large. These are known as perverse incentives; while virtually all subsidies start with good intentions, certain sectors and practices inevitably cause subsidies to devolve into being perverse.

Perverse incentives mostly impact environmental and societal health, thereby incurring long-term damage to economies. Examples include pollution, overexploitation of resources and landscape degradation. These environmental impacts can often have unintended, or at least unaccounted for, impacts on the physical and mental health of affected communities. Perverse incentives hide the true costs of unsustainable industries, and the externalities they create often incur high costs that are not reflected in the market prices of the products consumers purchase from these industries.

Perverse government subsidies are multifarious, appearing in many different forms across various economic sectors and industries. Arguably, the most egregious of these subsidies are directed towards the fossil fuel industry. Burning fossil fuels has been classified as the main contributor to global warming, and has historically been heavily subsidised by governments worldwide.

Even when a subsidy becomes perverse, it is difficult to decouple the government’s incentives from the targeted industry. This is because government subsidies can facilitate ingraining specific behaviours in consumers. An example of this phenomenon would be public transportation subsidies. A 2017 study on the effects of public transport subsidies in Estonia showed that public transportation use increased by 14% only a year after subsidies were implemented. Subsidies, even perverse ones, can direct consumers towards exhibiting certain practices or preferring certain behaviours. When these behaviours become linked to living standards, such as becoming accustomed to cheaply available gasoline, they can be notoriously difficult to change.

Eliminating these subsidies is a difficult proposition, but supporting unsustainable industries that damage the environment and community health is an untenable practice, especially considering the fossil fuel industry’s outsized share of global emissions contributions. By some estimates, in fact, removing global fossil fuel subsidies could reduce emission rates by between 6 and 13% by 2050. Ideally, governments would be able to shift subsidies to support more sustainable practices and businesses, although such attempts need to be complemented by adequate compensation mechanisms and social safety nets.

Quantifying Global Fossil Fuel Subsidies

The energy market has a long history of government intervention. Making energy and electricity cheaply available for consumers is a critical step for states to take when trying to modernise their societies and improve living standards. For many countries, the most cost-effective way to do so, at least historically, has been by subsidising the fossil fuel industry. Direct government subsidies towards the fossil fuel industry often take the form of tax credits and capital allowances.

You might also like: Denmark is Building an Artificial Island as a Clean Energy Hub

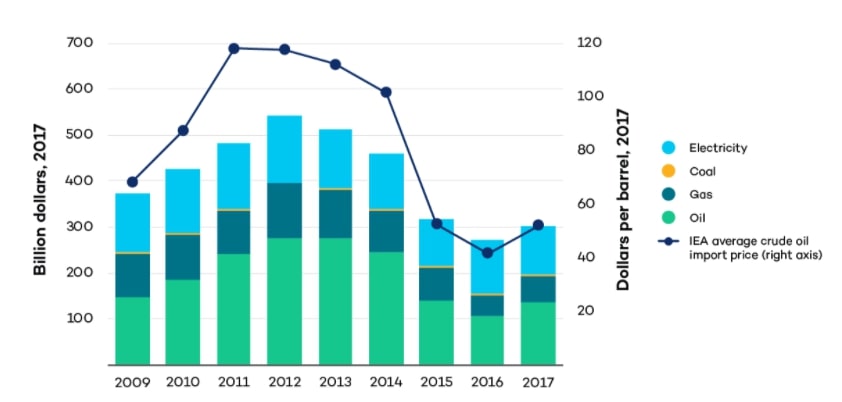

Fig. 1: Estimation of global fossil fuel consumption subsidies; IEA; 2018.

Calculating the total amount of direct government subsidies is not an exact science, and estimates tend to vary depending on what metrics are used. For instance, in 2014, the International Institute for Sustainable Development (IISD) estimated global fossil fuel subsidies to be around USD$548 billion. This estimate exclusively addressed the direct financial incentives governments used to underwrite the production and consumption of fossil fuels, and did not account for externalities related to environmental degradation and associated costs. Conversely, the International Monetary Fund reported in 2015 that global fossil fuel subsidies amounted to USD$5.3 trillion each year. The IMF’s estimate includes the costs of environmental damages and other negative externalities incurred by the fossil fuel industry, such as unpriced pollution, loss of ecological services and carbon emissions.

Some elements of the IMF’s analysis are certainly perplexing. For instance, the estimate includes costs incurred from traffic congestion, vehicular accidents and fatalities as externalities created by the subsidised use of gasoline. While these values admittedly stretch the meaning of the word ‘subsidy,’ the IMF’s report is important because it accounts for the externalised costs and strains that pollution and environmental degradation place on social and economic health.

The more conservative estimate employed by the IISD is useful when discussing the possibility of subsidy reform and shifts, since it is a more accurate indicator of how much governments are able to spend. However, accounting for negative externalities is critical, as it allows governments to understand the exact costs of unsustainable industries on the environment and society. Any discussion on subsidy reform needs to address the negative externalities that unsustainable industries inflict on the environment and the economy.

Fossil Fuel Subsidies and Inequality

Advocates of fossil fuel subsidies claim that, by lowering energy costs, the policy indirectly creates better living conditions for low-income members of society. Studies have shown that abrupt subsidy reform in otherwise inflexible markets can potentially lead to a loss of welfare for individuals and households in the short term. In the long term, however, subsidy reforms that shift government funds away from unsustainable industries such as fossil fuels tend to have overwhelmingly positive effects across the board, mainly because of productivity and efficiency gains through a reallocation of resources.

The argument that fossil fuel subsidies benefit the poor has several glaring issues. A 2010 report by the IMF analysed the social and economic implications of maintaining or removing fossil fuel subsidies. The report found that, while eliminating fossil fuel subsidies can lead to higher fuel costs for consumers and a short-term decline in welfare amongst all socio-economic groups, the decline in household spending power is always temporary. Economies also tend to rebound stronger than before when financial resources are reallocated more efficiently.

The report’s main findings, however, were that maintaining low fuel prices through subsidisation is a policy position that disproportionately benefits higher income groups. Since high-income businesses and individuals represent the lion’s share of an economy’s income and consumption, the wealthiest 20% of a population receives 43% of the economic and fiscal benefits created by fossil fuel subsidies, while the poorest 20% receives only 7% of benefits.

Fossil fuel subsidies have been criticised as an extremely inefficient way to improve social conditions. For example, in 2013, around 20% of Indonesia’s annual budget went towards fossil fuel subsidies, withholding funds that could have been used to finance more effective social programmes. This heavy subsidisation was despite the fact that two-thirds of poor Indonesian households did not consume any gasoline at all. A 2011 report by the IISD on the distribution of energy subsidy benefits by household income in Indonesia was reflective of the findings in the IMF’s report. In 2011, around 84% of the subsidised gasoline was consumed by the top half of households when organised by wealth, with 40% of gasoline use coming from the wealthiest decile. The poorest decile consumed less than 1% of the subsidised fuel.

Heavy fossil fuel subsidies change little in terms of quality of life for most people, because the vast majority of global emissions is produced by a distinct minority of the world’s population. Oxfam reported in 2020 how the richest 1% of the world contributes more than double the carbon emissions of the three billion people who make up the lowest income half of humanity. Lowering fuel costs only encourages wealthier households to buy more. By not targeting any specific group, fossil fuel subsidies are designed to primarily service the highest spenders in an economy.

As an economic instrument, subsidisation is an economic approach that exclusively encourages higher consumption behaviour amongst wealthier households. Since the benefits of subsidisation are primarily felt by the wealthiest strata of society, the entire practice functions to facilitate a trickle-down economic system. Subsidisation as a whole mainly benefits the largest spenders in an economy, marginalising low-income consumers. In addition to receiving paltry benefits from the subsidisation scheme, low-income communities become increasingly vulnerable to environmental degradation and other negative externalities when governments support the exploits of massive corporations involved in unscrupulous and unsustainable activities, such as the fossil fuel industry.

Despite a distinct lack of tangible benefits for the majority of a population, eliminating fossil fuel subsidies altogether is a delicate policy action to take, as such action can often elicit public protests against raised taxes, government austerity measures and higher rates of inequality.

In 2012, the Nigerian government decided to drastically slash its fossil fuel subsidies. As a result, cities erupted in widespread riots and protests led by citizens upset about higher fuel prices. In 2019, violent protests consumed the Ecuadorian capital of Quito due to the rapid removal of subsidies for gasoline and diesel, forcing the president to temporarily move Ecuador’s seat of government away from the city. Perhaps the most famous instance of public outcry over raised fuel prices were the yellow vests protests that began in France in 2018. These protests were triggered by the government’s plan to increase fuel taxes, a grievance that sparked cascading protests over wealth inequality and labour laws.

Image 1: Scenes of 2019 Ecuador protests against raised gasoline prices.

The circumstances of the protests outlined above and many more like them share commonalities that may indicate how government subsidies can be shifted to support more sustainable industries, without necessarily worsening inequality. For subsidy reform to happen successfully in any sector, particularly one that is as vital to quality of life as energy and fuel, certain conditions must be met. Gradual reform, fair distribution of resources and public trust in government are crucial for states to achieve lasting and equitable subsidy reform.

Reforming Fossil Fuel Subsidies

There is an argument to be made in support of completely scrapping fossil fuel subsidies, and for that matter any financial government intervention in the energy market, due to the falling costs of renewables and struggles of the fossil fuel industry to stay competitive. The renewable energy industry receives substantially lower subsidies than its fossil fuel counterpart. In 2018, the International Energy Agency estimated that global subsidies for fossil fuels were twice those directed towards renewable energy.

As market forces continue to organically make renewables more competitive, it is not an entirely unreasonable argument that removing energy subsidies entirely would be enough to encourage a more assured shift towards renewable energy.

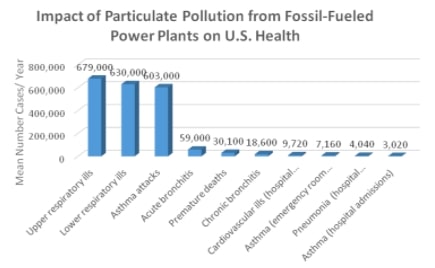

The issue with this approach is twofold. First, removing energy subsidies as a whole does little to address the costs incurred by the fossil fuel industry on external systems and institutions such as healthcare. A recent Greenpeace study found that, globally, air pollution from fossil fuels is directly responsible for 4.5 million deaths annually, and an estimated USD$2.9 trillion in economic losses, as much as 3.3% of global GDP. These losses are mostly tied to healthcare costs, which are paid for indirectly by consumers through taxation or medical expenses. Only removing direct energy subsidies would be a small and comparatively insignificant measure that fails to address where most of the externalised costs are coming from.

Fig. 2: Impact of fossil fuel-derived pollution on health conditions in the United States; Environmental and Energy Study Institute; 2019.

Secondly, any abrupt and absolute removal of subsidies without a solid and comprehensive alternative is virtually assured to cause socio-economic hardship and adaptation difficulties. In such a scenario, without a strategy to immediately replace low fuel costs, manifestations such as those seen in Nigeria, Ecuador and France would be commonplace.

Learning from what went wrong in these countries is critical to achieving a successful and gradual shift away from fossil fuel subsidies to support the efforts of more sustainable industries.

Critically, governments need to ensure that their actions are transparent and their citizenry trusts them. In Ecuador, the government had failed to keep promises regarding welfare payments to cushion the blow of raised gasoline prices. These payments were not delivered to people on time, aggravating the already-eroded public trust in government. Compensation mechanisms that are transparent, targeted and timely are crucial to achieving successful subsidy shifts.

Effective compensation packages should be targeted to groups that would be most affected in the short-term by higher prices, to ensure their public support and turn these segments into constituents. Countries such as Morocco, Ethiopia, the Philippines and Peru managed to successfully shift their fossil fuel subsidies to focus on renewables by implementing a conditional cash transfer policy and expanding educational opportunities and health insurance. Ghana also implemented a successful cash transfer programme to support the poor during its own subsidy reform period, as well as ramping up investments into its healthcare system.

Fig. 3: Countries and fossil fuel subsidies reform between 2015-18; Global Sustainability Initiative; 2019.

Amassing public support and eliciting positive dialogue from citizens can be done by drafting and publicising comprehensive plans detailing where fossil fuel subsidy funds will be shifted to. In Indonesia, for instance, President Joko Widodo made subsidy reform central to his successful election campaign in 2014, explaining clearly how the national budget would increase by over USD$15 billion, and would be redirected towards improvements in transportation, infrastructure and public safety nets for the poor.

Shifting fossil fuel subsidies will always be a delicate process. However, for governments seeking an opening to reduce or remove these subsidies, market forces and other dynamics have made 2021 an ideal time to do so. Oil prices have been in a gradual decline over the past decade, and have fallen to record lows as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic. Naturally low oil prices present a perfect opportunity to reduce fossil fuel subsidies, since consumers would not be burdened by excessive price hikes in the case of subsidy removal. Economists have rallied behind the idea of governments taking advantage of the current oil slump to reduce their subsidies, calls that only intensified in 2020.

Featured image by: Flickr