Nowhere are climate change impacts and environmental decay more apparent than in the Global South. When a country’s government needs to direct all its resources towards improving basic living standards, some environmental degradation through deforestation, pollution, land-use changes and infrastructure development is unavoidable. In most cases, the governments of developing countries shoulder such intense financial responsibilities that they cannot afford to preserve biodiversity and natural capital. To pursue more ambitious environmental policy, developing nations often require a financial incentive that allows governments to shift their priorities. Debt-for-nature swaps are financial mechanisms that allow portions of a developing country’s foreign debt to be forgiven, in exchange for commitments to invest in biodiversity conservation and environmental policy measures. In 2021, the global financial crisis induced by the COVID-19 pandemic creates a singular opportunity for debt restructuring with a focus on environmental preservation and climate resilience.

—

Preserving ecosystems is a critical linchpin to maintaining public health, quality of life and growth. Preserving intact and healthy ecosystems and biodiversity allows ecological services,-the social and economic benefits humans can derive from nature- to flourish. Clean air, abundant freshwater and fertile soil are just some of the countless ecological services that are vital to development.

External forces such as human activity and consequent climate change have damaged the stability of ecosystems, and will continue to drive biodiversity loss over the coming decades, with the OECD estimating terrestrial biodiversity will decrease a further 10% by 2050. For Global South countries, whose economies remain heavily reliant on agriculture and natural resource exploitation, any loss of ecological services has a serious impact on economies and people. Agricultural economies which still lack a particularly specialised or skilled workforce, a properly developed industrial sector or widespread access to education are often unable to compensate for deteriorating ecological services.

Developing nations therefore have a difficult choice to make. While protecting the integrity of ecological services and preserving natural capital for future and domestic use is ideal, the costs of leaving land and resources undeveloped are too high.

With current market conditions, developing nations are hard pressed to find a suitable, and more importantly cost-efficient, alternative to overexploitation of natural resources. In lieu of systemic changes in how nations can pursue methods of strategic economic growth, market mechanisms have been employed to alleviate the financial burdens of developing countries and incentivise positive climate and conservation action.

Debt-for-nature swaps are as the name suggests- a debtor country is allowed substantial discounts on the debt owed to its creditor in exchange for investments towards conservation and enacting environmental protection measures. A swap for a debtor country’s foreign debt can involve a creditor country, a creditor commercial bank or an environmental non-governmental organisation acting as a broker.

While these policies have generally been successful in promoting environmental conservation, they have also come under fire for exacerbating existing wealth and social inequalities in developing nations, and a perceived lack of effectiveness relative to other transnational financial mechanisms. As global debt rates continue to rise, however, innovative financial mechanisms are needed to safeguard developing countries from worsening economic, health and environmental circumstances.

You might also like: The ’15-Minute City’ Model: Encouraging Sustainable Cities

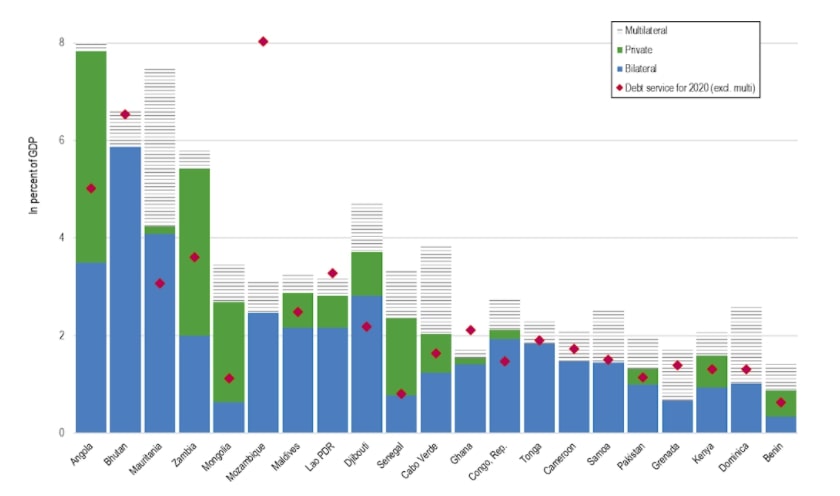

Fig. 1: Debt payments as a percentage of GDP expected by country in 2021; World Bank; 2020.

Foreign Debt & Environmental Policy

Debt-for-nature swaps only really work when debtor countries are at a high risk of defaulting on their payments, and therefore debt buyers can purchase outstanding debt for significantly discounted prices at well below face value. This prerequisite characteristic for swaps to work emerged in 1982, when a secondary market was formed that allowed banks to sell and trade foreign debt at discounted rates. In the early 1980s, in the midst of the Latin American debt crisis, many developing countries had taken out substantive loans from commercial banks or foreign governments, and there was a growing concern that most of the accumulated debt would never be fully serviced or repaid, and was therefore not worth its face value, incentivising creditors to sell or trade their debt instruments at discounted rates.

In the case of debt-for-nature swaps, creditor entities can employ the secondary market to divest their outstanding loan payments to NGOs at discounted rates by lowering the interest rate, changing the currency of the debt amount or refinancing the debt at a current lower market value. Since debt-for-nature swaps create a relatively easy exit from debt payments at a high risk of defaulting, they are often beneficial to all involved parties. For debtor countries, they become at least partially free of their burdensome foreign debt. For creditor entities, they are able to absolve themselves of high-risk debt relations.

In 1987, the environmental NGO Conservation International arranged the world’s first debt-for-nature swap, forgiving a portion of Bolivia’s foreign debt. The agreement cancelled USD$650 000 of Bolivia’s debt. In exchange, the Bolivian government agreed to set aside 3.7 million acres of land adjacent to the Amazon Basin for conservation purposes. This exchange is an example of a three-party swap, which involves a debtor, a creditor and an environmental NGO acting as a broker. In addition to Conservation International, the Nature Conservancy and WWF have been frequent mediators of debt-for-nature swaps.

In a three-party swap, an NGO purchases an outstanding debt from the creditor through the secondary market at significantly discounted rates, and then renegotiates the debt obligation with the debtor country. The NGO then sells the debt back to the debtor country for a higher price than it was bought by the NGO but still significantly lower than the original payment the debtor country would have had to make. When the debtor repurchases its debt, the obligation is forgiven, and some of the leftover capital that would have gone into paying off the original commitment are funnelled into grants, bonds or funds that will be directed towards pre-agreed upon conservation investments or enacting environmental policies.

Fig. 2: Visualisation of three party debt-for-nature swap; Congressional Research Services, 2010.

In addition to three-party swaps, bilateral swaps directly between debtor and creditor countries have become increasingly popular. With this type of swap, a creditor country usually restructures a portion of a country’s obligations, or sells the debt to the debtor at a discount. Funds for conservation or environmental policy initiatives are raised through interest payments on restructured debt or from the debtor country’s leftover reserves after purchasing their debt at a discounted price. Bilateral swaps can also be multilateral, involving multiple countries. An example of this occurred in Poland in 1992, when Finland, Sweden, Norway, France, Italy, Switzerland and the US agreed to restructure a portion of Poland’s debt. This swap led to the foundation of the non-profit ‘EcoFund,’ which by 2003 had received $580 million, designated to protect Poland’s biodiversity, manage waste, reduce greenhouse gas emissions and prevent soil contamination.

Since debt can be purchased at well below its face value, large portions of a country’s foreign debt can be forgiven by allocating relatively small amounts of money from creditor governments and NGOs.. For instance, the US and Peru engaged in a bilateral swap in 2002, which was subsidised by several NGOs. The Nature Conservancy, Conservation International and WWF donated a total of $1.1 million, while the US government allocated $5.5 million to forgive a portion of Peru’s debt to the United States. Since Peru’s foreign debt could be purchased and forgiven at discounted rates well below its face value, these investments allowed a total of $14.3 million of Peru’s foreign debt to be forgiven between 2002 and 2018, of which $10.6 million was to be set aside for conservation projects.

While bilateral and multilateral swaps are led by states, environmental NGOs continue to play an important role in these initiatives, contributing expertise and services in facilitating a country’s investments towards conservation measures. The major difference between these swaps and the three-party variants is that, in bilateral or multilateral agreements, creditors normally decide what policy agenda will be enacted in the debtor country. In three-party swaps, NGOs tend to collaborate closely with debtors and local governments to decide what measures should be implemented.

A 2010 US Congressional research report estimated that, between 1987 and 2010, $170 million in face value debt had been purchased globally for $49 million in three-party swaps. These transactions generated around $140 million in local currency funds for debtor countries to redirect towards conservation projects. In terms of bilateral swaps, the same report estimated that in the early 1990s, the US had restructured debt equivalent to a face value of close to $1 billion. These deals generated nearly $178 million in local currency that debtor countries used to fund environmental, natural resource, health protection and child development projects.

While debt-for-nature swaps have waned in popularity somewhat since the 1990s, they continue to be employed in innovative ways across the world. In 2018, the Seychelles collaborated with the United Nations Development Programme, the Global Environment Facility and the Nature Conservancy to forgive $27 million of its debt. This debt swap was notable for being the first of its kind to focus on marine ecosystem and biodiversity conservation, protecting up to 400 000km² of ocean.

Image 1: New protected areas of Seychelles water as a result of debt-for-nature swap; Seychelles government, MEECC Geodatabase, The Nature Conservancy, ESRI; 2018.

Criticisms of Debt-for-Nature Swaps

Despite being generally viewed as successful and substantive financial mechanisms to achieve strong environmental policy outcomes, debt-for-nature swaps have never been able to garner widespread appeal and recognition. Concerns have been raised by international observers over the perceived inefficiency of debt-for-nature swaps when compared to other financial mechanisms, as well as the potential risks that debt relief deals pose to a developing country’s sovereignty.

The United Nations Development Programme released a report in 2017 overviewing the practice and evaluating the benefits and potential risks of debt-for-nature swaps. While the UNDP found that swaps could measurably improve a country’s credit standing and grant its government access to important financial services for economic and social development, the risks and relative inefficiencies associated with poorly implemented swap deals can be significant.

With regards to inefficiency, debt-for-nature swaps can often take years of expensive negotiations to come to fruition. Particularly time-consuming are negotiations between debtor and creditor countries over the scope of conservation measures. Delays increase the cost of operations, and negotiations may never come to a satisfying conclusion, raising the question as to whether the time and capital needed to complete these deals would be better spent elsewhere.

The problems of debt-for-nature swaps’ time-consuming nature are compounded by the inherent financial risks of such operations. These deals are marked by constant risks associated with fluctuating exchange rates, inflation and the potential for fiscal or liquidity crises in debtor countries. Despite the potential complications, these challenges can often be at least mitigated. For instance, fixing exchange rates for the terms of the deal well in advance of the actual payment date can ensure that costs will not be affected by market fluctuations. For these swaps to be successful, they require competent planning and commitments by all parties to abide by any agreement made.

This last point raises another potential concern. Some observers have raised concerns over debtor countries’ potential loss of legislative leverage and sovereignty to foreign entities, especially when bilateral or multilateral swaps are employed. With these swaps, any grants, bonds or funds set aside will be according to the preferences and agenda of the creditor entity, which may not consistently align with local conservation needs. If not handled correctly, these dealings can easily create animosity and apprehension between nations that would otherwise mutually benefit from a swap deal.

Following the early success of the swap deal arranged in Bolivia, NGOs and US policymakers turned their attention towards making a similar deal with Brazil in 1989. At the time, Brazil was a prime candidate for a debt-for-nature swap; the country possessed 30% of the world’s rainforests, and almost 10% of the Global South’s total foreign debt. Despite advanced negotiations for up to $8 billion of Brazil’s foreign debt to be forgiven, the country’s leaders opted at the last minute to close off the Amazon from any direct financial aid from foreign governments, citing concerns over a misalignment of interests and a perceived lack of concern for Brazil’s overwhelming social and economic problems.

The case in Brazil illustrates why having bilateral agreements can complicate matters more than a three-party swap might. Nationalistic pride, maintaining political sovereignty and concerns over preserving enough resources for domestic development are the primary barriers faced by debt-for-nature swaps. Especially in Global South countries, where apprehension towards former colonial powers may still run strong, debt-for-nature swaps need to be planned and managed competently, and framed primarily as business deals to deliberately depoliticise them. In this context, three-party swaps may be more effective than their multilateral counterparts, since NGOs do not impose foreign agendas and work more closely with local governments to meet domestic needs.

Concerns have also been raised over the risk of corruption and the misallocation of resources by governments of low-income countries. Debt relief in transitional countries without stable governments can potentially end up favouring elites and widening inequalities. A 2012 study examined the negative social fallout of the 1987 Bolivian swap deal, a 1989 bilateral swap between the US and Madagascar and a 1990 three-party swap in Costa Rica. In each country, the binding nature of the swap deals left many indigenous peoples and sustenance farmers landless and mired in poverty. In Costa Rica, displaced farmers had to resort to illegal poaching, logging and mining to support themselves. While some trade-offs between development and conservation must be expected, debt-for-nature swaps that exacerbate poverty and worsen living conditions defeat their own purpose.

In light of these challenges, some observers have called for the use of alternative financial mechanisms that, while not explicitly geared towards environmental conservation, may be more efficient in alleviating debt burdens and promoting socio-economic growth. For instance, the IMF and the World Bank jointly sponsor an initiative that supports heavily indebted poor countries through comprehensive debt relief packages, which between 1996 and 2017 provided $76 billion in debt services to 36 countries worldwide.

The issue with these programmes is that they lack a unique and important characteristic of debt-for-nature swaps: the ability to financially engage institutions that would otherwise be uninvolved in conservation and environmental policy initiatives. As the costs of climate change and environmental degradation for Global South countries rise, it becomes critical to involve the financial and political strength of all types of institutions to avoid debt and climate crises alike.

Debt Restructuring in 2021

2020 marked the year governments worldwide began to seriously discuss the importance of incorporating environmental legislation into their economic and political agendas. States have understood that recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic provides an opportunity to address environmental justice, green jobs, conservation initiatives and climate resilience.

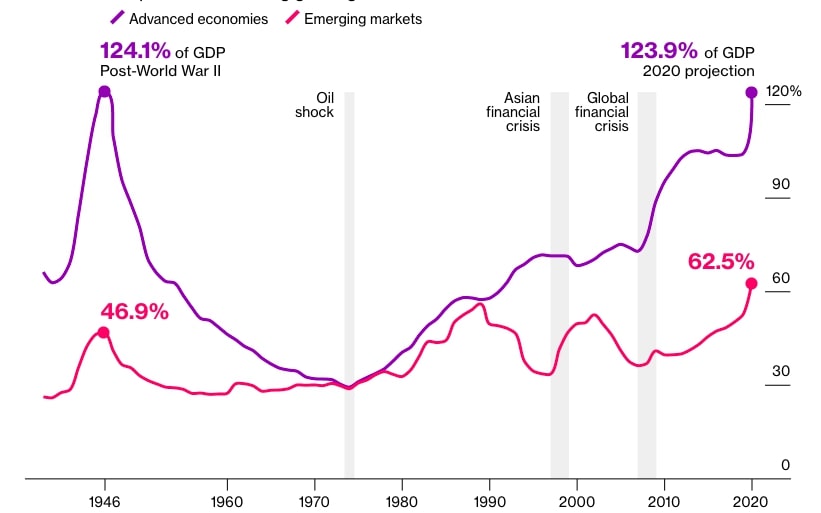

In addition to the current health crisis and the ever-present climate crisis, the pandemic is placing unprecedented strain on the fiscal institutions and budgets of countries worldwide. Debt skyrocketed in 2020, adding an estimated $19.5 trillion to global deficits.

Fig. 1: Global debt as a percentage of GDP from 1946 through to end of 2020; International Monetary Fund Fiscal Monitor, October 2020.

Debt spikes in emerging markets were slightly less dramatic than in mature economies, although reached unprecedented levels nonetheless. In October 2020, the IMF and the World Bank convened for their annual fiscal outlook summit. There, Kristalina Georgieva, managing director of the IMF, noted that low-income countries “entered this crisis with already high debt levels, and this burden has only become heavier.”

Creditors have acknowledged that debt payment commitments in the short term are unlikely to be upheld, although have stopped short of forgiving them or transferring the debt to finance environmental protection measures. In May 2020, G20 countries agreed to establish a Debt Service Suspension Initiative (DSSI), with the World Bank and the IMF. The initiative allows developing countries to employ all of their financial resources to protect their citizens from the pandemic by suspending their scheduled debt payments to creditors. Between its inception and February 2021, the DSSI has generated around $5 billion in relief funds for over 40 countries worldwide.

Suspending debt payments and offering temporary relief is frankly the minimum that could be done, from both a moralistic as well as a more utilitarian standpoint. At the moment, creditors are simply failing to seize the opportunity amidst the crisis. A creditor who elects to take up the mantle of debt forgiver and push through debt-for-nature swaps in 2021 would gain tremendous reputational influence and soft power reach.

The country which could stand to gain the most soft power from the current debt crisis is certainly China, whose economy has not suffered nearly as much during the pandemic as its major rivals, the EU and the US, and is projected to lead global economic recovery in 2021. China has been seeking to expand its soft power reach for years, and aims to become the torchbearer for global climate action in the near future. The current debt crisis presents China with a singular opportunity to do just that and act on its ambitions.

A 2021 study showed how, of the 46 countries that have thus far participated in the DSSI, 68% of official bilateral debt payments originally scheduled to be issued in 2020 were owed to China, totalling around $8.4 billion. Angola, Myanmar, Cambodia and the Solomon Islands are just a few of the countries which have received substantial loans from China in recent years, and where biodiversity and climate threats are high.

This number may be high, but it may actually be dwarfed by the real total that the world owes China. China does not report on its international lending, and since the Chinese commercial banks that act as foreign creditors are all state-owned, global debt towards China has become ‘hidden’, marked by consistent systemic underreporting. By some estimates, global debt owed to China amounts to $1.5 trillion between direct loans and trade credits, owed by over 150 countries.

Fig. 2: Estimate of global debt owed to top crediting countries between 2019 and 2021; World Resources Institute; 2020.

Concerted effort by China to engage in such debt forgiveness arrangements would be immensely beneficial to its international standing, and could complement its domestic goal to become carbon neutral by 2060. Debt-for-nature swaps in the wake of COVID-19 should depart slightly from the original goals of these swaps, and become debt-for-climate swaps which are focused more specifically on climate resilience.

Debt-for-climate commitments from Global South countries can easily meld climate and healthcare investments to improve resilience against climate change as well as the current pandemic and future health crises. This can include bolstering disaster risk finance institutions, such as disaster funds, fast-disbursing loans to affected areas and parametric insurance policies. Governments can also create dedicated climate funds that retrofit medical structures and healthcare infrastructure to be more resilient and protect against climate impacts as well as health emergencies.

While China’s actions will be crucial to restructuring global debt to improve climate resilience worldwide, similar actions can be taken by all major creditors. Despite the shortcomings and complications of swapping foreign debt for environmental policy commitments, the practice is able to incentivise and engage financial and commercial institutions that would otherwise presumably be actively exacerbating the climate crisis. When planned competently and with equity in mind, debt swaps can play a small but important role in improving health and environmental standards in developing countries worldwide.