The US aims to achieve an emissions reduction target of 50-52% from 2005 levels in net greenhouse gas emissions by 2030. This is the new national goal declared by President Joe Biden at the Leaders’ Summit on Climate convened on Earth Day 2021. The new goal represents a return of the US to the fore of global environmental diplomacy and coordinated efforts to tackle climate change, after four years of indifference under predecessor Donald Trump. Calls to halve the country’s emissions have been coming from business and scientific circles alike, but how does the US’s new goal compare to the targets of similarly developed countries, and does it accomplish Biden’s primary goal of repositioning the US as a global leader on climate policy?

—

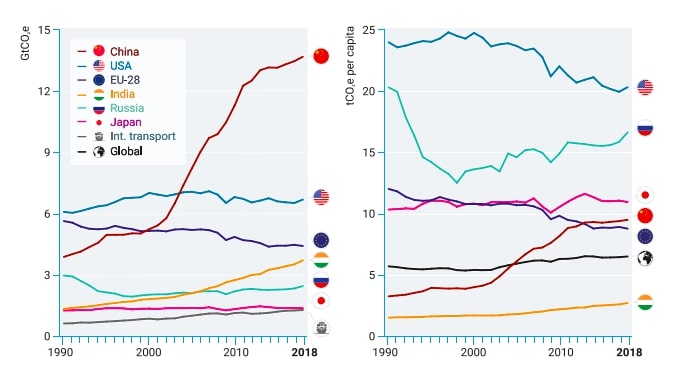

In announcing the US’s new nationally determined contribution (NDC) to reduce its greenhouse gas emissions, Biden had to juggle several important expectations from the global community. The US is the second highest current emitter of greenhouse gases in the world, behind China, but is also the country with the highest cumulative rate of historical emissions over time. Additionally, the US accounts for the highest per capita rate of emissions in the world amongst countries with large populations.

You might also like: The Leaders’ Summit on Climate 2021: A Summary

Figure 1: Top greenhouse gas emitters worldwide on an absolute basis (left) and per capita (right); UN Environment Programme; 2019.

It is therefore imperative that the US play an active part in any international efforts to counter climate change. Biden’s announcement and rhetoric thus far has garnered international commendation, but also skepticism over the pledge’s durability. A target to reduce greenhouse gas emissions in the US by half is a technically feasible goal, but the political climate in the US presents certain roadblocks that other countries, either because of political system or culture, do not have to deal with.

But the announcement is certainly a step in the right direction, and it makes the US one of the more ambitious advanced economies in terms of reduction targets. Will the new NDC be enough for the US to lay a credible claim to global leadership on climate policy, and what do Biden and his administration still have to accomplish to turn their target into actionable reality?

How Biden’s Goal Stacks Up

In a recent interview with the New York Times, Nathaniel Keohane, an economist and senior vice president for climate at the Environmental Defense Fund, discussed Biden’s new international climate commitments.

“This matched the level of ambition that we’ve been calling for, and that the business community has been calling for. We’re seeing an administration that is willing to go bold when the moment demands it,” Keohane said, adding that the new NDC is, “in the top tier of ambition globally- not quite as ambitious as the EU, and not nearly as ambitious as the UK. But it compares favourably with the rest of the world, and it puts the US in the top tier, which is where it should be as the largest historical emitter over time and as the second-largest emitter today.”

A 50% reduction target certainly places the US in the top tier of global ambition. The chart below shows how the US’s new target compares to the announced pledges of similar advanced economies. While still trailing the targets of the EU and the UK, the US can now be placed in their same ambitious group, and is well ahead of other developed countries such as Japan, Canada and Australia.

Figure 2: US 2030 emissions reduction target of 52% compared to plans from other advanced economies, with 2005 and 1990 baselines; Data by Rhodium Group and UNFCCC, visuals by the New York Times; 2021.

Biden’s climate summit was also intended to encourage other nations to announce more ambitious targets themselves, a goal that partially succeeded. Canada raised its targets to reduce emissions by 40-45% from 30%, and Japan announced that it would cut its emissions by 46% from 2013 levels by 2030, up from its original 26% target. South Korea, China and Brazil also made noteworthy announcements at the summit, but did not provide updated NDCs or any hard emissions reduction targets.

But even considering the updated ambition of Canada and Japan, the US’s new target remains heads and shoulders above that of most of its peers. The US is now largely on level terms with the EU in terms of ambition, although much will depend on domestic policy developments over the coming months, but trails behind the efforts of the most ambitious actor, the UK.

Shortly before the summit, the UK announced that it would strengthen its already high target, and is now aiming to achieve an emissions reduction of 78% by 2035 compared to 1990 levels. Upon announcing this new target, Prime Minister Boris Johnson said: “We want to continue to raise the bar on tackling climate change, and that’s why we’re setting the most ambitious target to cut emissions in the world.” The UK has managed to reduce its emissions between 1990 and 2019 by 44%, mainly by focusing on reducing fossil fuel use and investing in renewable energy.

The US’s new target places it well ahead of its most serious economic and political rival, China, at least within the sphere of action taken to mitigate climate change. China, the world’s largest emitter of greenhouse gases, has made the noteworthy pledges to reach peak emissions by 2030, and to achieve carbon neutrality by 2060. However, the country has yet to provide a satisfactory roadmap of how it intends to reach these targets, especially considering it remains by far the world’s biggest coal consumer, and is ramping up– not reducing- the construction of new coal-fired plants.

China has laid out some targets that address a clean energy standard, renewable energy investments, regulated use of pollutant chemicals and CO2 sequestration initiatives, but has refrained from declaring any specific cuts to emissions within the next decade. Chinese leaders have often claimed that, because China began industrialising later than most Western countries, it should be held to a different standard than the US and Europe. “When it comes to climate change response, China is at a different stage than the U.S., Western nations and other developed countries,” Le Yucheng, China’s vice foreign minister, said in a recent interview with the Associated Press.

For China, a challenge is that leaders must balance expectations of economic growth with reducing fossil fuel use. China’s rampant economic growth makes specific targets unappealing to policymakers. Other rapidly developing countries are in a similar situation to China. India, for instance, has set targets concerning renewable energy growth, but failed to offer any clear indications on emission cuts at Biden’s summit.

As a more mature economy, the US has the ability to make more ambitious promises and more actionable short-term impacts than many of its bigger and wealthier rivals. Countries including China, India and Russia reiterated commitments to fighting climate change and pursuing international cooperation between states, but did not announce any clear targets at the summit. For Biden, meanwhile, the summit was largely a win, as the US was able to announce an ambitious new target flanked by similarly positive updates from its closest allies, while the principal rivals to the US largely stalled for more time or reiterated old promises without really offering anything new. The US, along with Canada, Japan and the UK, will need to implement policy to match their ambitious goals, but the summit certainly helped the US in its quest to reclaim credibility and a role as global climate leader.

How Good is Good Enough?

Some hurdles remain for the US to claim enough international credibility to consider itself a global leader in climate action, and for its targets to measure up globally. A 50% reduction target is very promising, but it will need to be backed up by equally ambitious domestic economic policy to achieve any real results. In the early weeks and months of his term, Biden has been attempting to convince the rest of the world that executive action can effectively get legislation passed in the US without having to rely on Congress and the support of the Republican Party, a group that has rarely proven agreeable on ambitious climate action.

But Congress would still need to be involved in most aspects of Biden’s legislative plan for countering climate change, especially where increases in spending and federal funding is concerned. There are some arcane and controversial policy measures Biden could implement to push through his most ambitious proposals, but the risk of legislation getting bogged down by unconstructive debate is more real than it has ever been in the US.

Additionally, world leaders are justifiably concerned about the durability of any policy Biden would be able to push through, given that the next presidential administration could swoop in and rescind any progress made under Biden. After former President Barack Obama’s efforts to make the Paris Agreement a reality, Donald Trump was able to single-handedly change the entire direction of US climate policy for four years upon taking office. Neither was this the first time the US walked back on its climate commitments following an administration change. President Bill Clinton and Vice-President Al Gore played instrumental roles in brokering the 1997 Kyoto Protocol to reduce global greenhouse gas emissions, but in March 2001, just a few short months after taking office, George W. Bush declared that the US would no longer be party to the agreement.

This is not, as some may say, an inherent problem with democratically elected governments. Of course, officials in more autocratic governments with a single ruling party such as China may have an edge in times of crises because of their ability to plan far ahead. But even in Western European countries, which are all led by democratically elected leaders, there is a remarkable consistency in climate change policy, at least relative to the US. Climate change persistently ranks as the top public concern for European citizens, and climate action has rarely been as partisan or politicised in Europe as in the US, a country whose political polarisation is virtually unmatched anywhere in the world.

For Biden, the mission seems to be to stretch executive action as far as it can go, enshrine policies in irreversible law and compromise with the Republican Party where possible without wasting time. The Republicans appear to have become almost dogmatically opposed to increased spending, government regulation and progressive action to counter climate change. Overcoming these bureaucratic obstacles, convincing the public of the importance of mitigating climate change and ensuring that future leaders cannot unilaterally undo any progress made will be key for Biden to ensure that his goals measure up to those of the rest of the world.

There is another challenge that the US and the rest of the world will soon have to contend with. The ultimate goal for every country and every leader declaring a commitment to reduce emissions is to, eventually, reach a point of net-zero emissions. The spate of net-zero pledges that have emerged over the past year all aim to arrive at this point by around 2050, the international gold standard for emissions reduction targets. If the world is unable to meet this goal, it will be virtually impossible to keep temperature rise below 1.5°C and stave off the worst effects of climate change.

How many of these countries are actually close to achieving this? Unfortunately, the answer is almost none. More than 110 countries have made a pledge to reach carbon neutrality by mid-century, including the world’s major emitters, several have made their net-zero targets legally binding and two countries, tiny Bhutan and Suriname, are already carbon-negative, absorbing more CO2 than they emit. But while pledges and commitments abound, there has so far been precious little actionable policy that illustrates a roadmap for individual countries to reach carbon neutrality.

Figure 3: 2100 warming projections with current policies, climate pledges and stated net-zero targets; Climate Action Tracker; 2020.

To understand how the US’s goal measures up to its carbon neutrality target, it may be useful to look at the UK’s recently announced updated goal. In 2020, the Climate Change Committee, a British independent public body, recommended that the UK reduce its emissions by 78% by 2035. The Climate Change Committee reported that the UK’s previous goal, a reduction of 68% by 2030, would not be sufficient to reach net-zero by 2050.

A 78% reduction for the UK is necessary to meet its national target to reach net-zero emissions by 2050, an objective and timeline shared by Biden. A recent analysis by Climate Action Tracker found that the US would need to lower emissions by at least 57% by 2030 in order to reach carbon neutrality in 2050. Biden’s current target of 50-52% may be close, but in the case of global temperature rise, every fraction of a degree counts. Some environmental groups have gone even further, calling for a 70% reduction in emissions to account for the US’s high rates of historical emissions and emissions per capita. Such a target would address a moral responsibility for the US to be held accountable for its historical emissions, and to compensate for the inability of developing countries to reduce their own emissions within the required timeframe while maintaining adequate quality of life standards.

While Biden’s current goal may not be sufficient to reach a 2050 net-zero target, the beauty of NDCs is that they are designed to be provisional, and then progressively built upon and improved with further ambition as new technologies emerge and priorities become more consolidated. Much like the UK was able to announce an updated NDC this year when presented with new data, the US is capable of doing the same if the country begins to politically internalise the gravity of climate change.

The signs are encouraging: a 2020 survey, for instance, found that two thirds of Americans- and over half of Republicans- believed that the government should be doing more to fight climate change. If Biden can stimulate the political will to address climate change, and if the Republican Party begins listening to its voters rather than its precepts, it is not inconceivable for even more ambitious action to be on the horizon.

Featured image by: Flickr