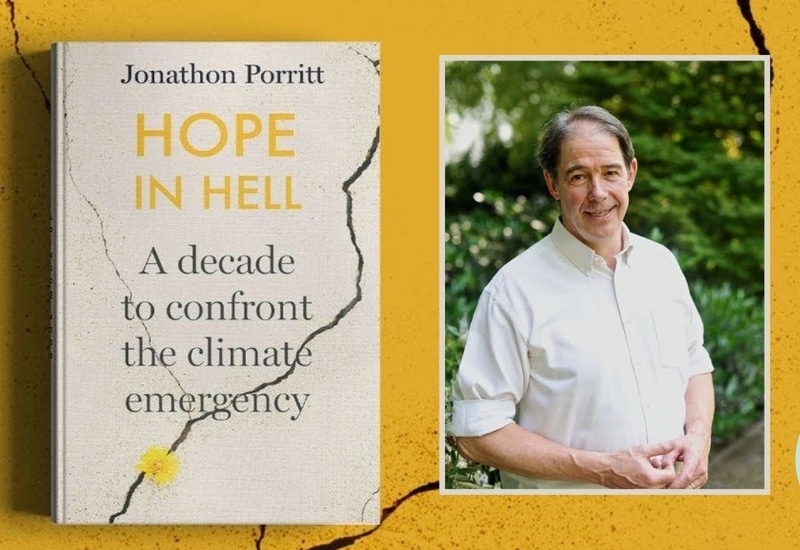

Few people have been as actively engaged on all fronts of British climate activism and action over the past four decades as Sir Jonathon Porritt. As the former chair of the Green Party of England and Wales in the 1980s, and co-founder of the influential environmental and sustainable development charity Forum for the Future, Sir Porritt has made a name for himself as one of Britain’s most experienced environmentalists. In his newest book Hope in Hell, Sir Porritt brings his experience from working with both the public and private sector to the fore, and outlines what we should expect from the near future. In this ultimately hopeful book, Sir Porritt deciphers the environmental challenges we still face, what needs to be done to meet them and why we might allow ourselves to be hopeful that we can actually do so.

—

The next decade will be crucial for us to limit global warming to 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels. This view is one shared by Sir Jonathon Porritt and many other experts in the field, and it is a timeline that is employed as a guiding principle throughout Hope in Hell. In the first part of his book, Sir Porritt summarises the science behind how we got to where we are, who is responsible for emissions and what the eventual consequences of our unchecked actions will be. In the second part of his book, Sir Porritt delves into the means, knowledge and technology we can employ to mitigate these consequences, stating that all these solutions are already available and ready to use- we just need to find the will to enact them.

Critical to achieving Sir Porritt’s vision of the future is technology, specifically pertaining to renewable energy capacity. The author is tellingly enthusiastic about the recent leaps and bounds of the solar and wind industries, and the promising room for future growth and falling costs both sources boast. The technical fixes exist and they are becoming increasingly easy to scale cheaply. The problem, Sir Porritt says, is that there are several ‘incumbents’ in our current system of governance, in the shape of powerful and entrenched ‘inactivists’ such as the fossil fuel industry. These powerful actors are the most egregious perpetrators of global emissions and environmental degradation, and their incumbency means that they have the ability to stymie any potential political and social will to implement the solutions we need.

But all hope is not lost, Sir Porritt insists. The window of opportunity to overcome these incumbencies and create meaningful change is certainly closing, but it is still open. He draws hope not only from technology but from youth; from their movements for climate action, from the critical mass they have acquired and the uncompromising stances taken by young leaders such as Greta Thunberg.

Porrit unabashedly denounces and rejects ‘disaster speak,’ opting instead to employ hopeful rhetoric. This choice makes the book refreshingly readable, helped by the fact that Sir Porritt largely avoids the use of scientific jargon, and satisfyingly explains the technical terms he deems necessary. Hope in Hell serves as an excellent primer for those relatively new to the environmental movement and the intricacies of climate change, although may offer little in the way of new information or arguments to the reader who is already well versed in the area.

You might also like: Court Ends Donald Trump’s Attempt to Allow Drilling in Atlantic and Arctic Oceans

The most interesting views Sir Jonathon Porritt espouses in his novel relate to his changing beliefs of how climate activism itself needs to change. As a figure who has famously gone to great lengths to cooperate with politicians and businesses alike to reach constructive outcomes, Sir Porritt has come to accept that more radical action is needed in the fight to counter the climate emergency.

What this more radical action should look like depends on the individual, but the primary message Sir Porritt appears to be mediating is that we cannot afford for anyone to be a passive bystander anymore. Extreme climate pessimism, a defeatist attitude that says that we are doomed and no behavioural change could ever save us, and extreme climate optimism, the belief that we don’t need to change our behaviour because there are higher forces at work that will ultimately save us, are equally damning to our prospects of tackling climate change. Everyone has a role to play in countering the climate crisis, and everyone has the moral responsibility to understand what that role is. Just don’t do nothing, essentially.

Nobody has the luxury to be a bystander anymore, this much is certainly true, and Sir Porritt articulates this notion well. But if radical action is truly what is needed, then Hope in Hell can be at times too elusive in accurately defining what steps have to be taken to make the change needed possible. The roadblocks to achieving a sustainable future are laid out clearly, but the book can be reticent in offering details on how to remove them, a sometimes frustrating choice given the urgency of the crisis and how fast our window of opportunity is closing.

Perhaps it is the youth movements that Sir Jonathon Porritt is so fond of that will prompt the biggest change. Younger generations are the most willing to unceremoniously abandon the incumbent powers, and are the most open to embodying the necessary adjustments to how humans live their lives. Innovation is fantastic and necessary, but technology alone will not save us without institutional reform and the social and political will to upheave current systems and replace them with what is better. If youth can be what enacts this transformation, then maybe there really is reason to hope.

For more, watch Sir Jonathon Porritt speak with Earth.Org Editor Deena Robinson in a fascinating hour-long conversation here.

Hope in Hell

Sir Jonathon Porritt

2020 , Simon & Schuster, 312pp